Learning to *be*

How schools overlook the most important kind of learning

In my last post, I questioned some of the standard definitions of learning that do the rounds in edublogosphere. Here are three examples::

“Learning is the acquisition, retention and transfer of knowledge and skills.”

“If nothing has changed in long-term memory, nothing has been learned.”

“Learning is the acquisition of skill or knowledge, while memory is the expression of what you’ve acquired.”

A few people pushed back on my assertion that these definitions are a bit narrow, and fail to capture the essence of learning in all of its multidimensional glory. Here are three of the comments I received:

“I wonder if we need a succinct definition of learning? Learning happens regardless of this.”

“So what? We all enjoy our particular takes and endeavour to persuade others of their unique merit.”

“I know when I’ve learned something. Can’t be that hard.”

This is a strong challenge which I’ve reflected on a lot over the last couple of weeks. And I’ve arrived at an answer which I think touches on something important.

Hold on to your hats!

The cognitive turn

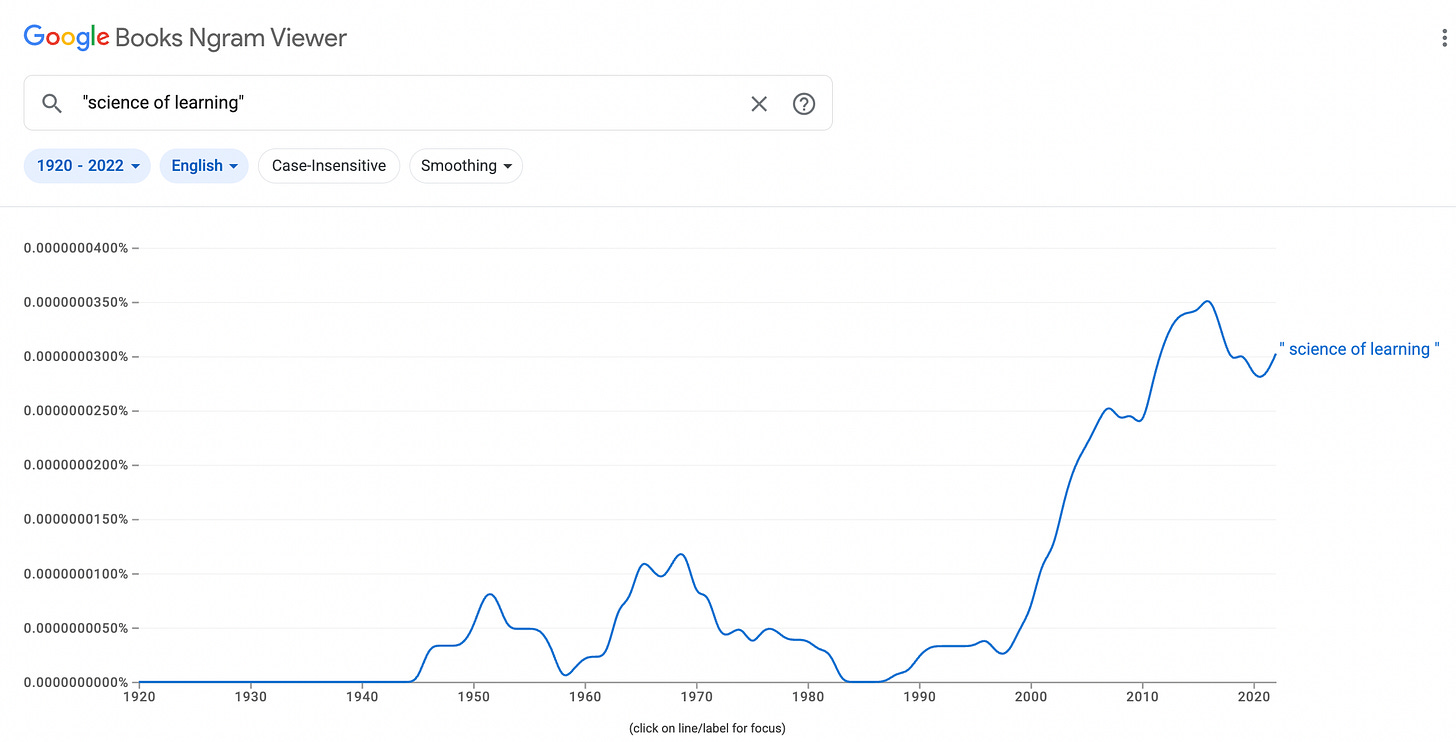

In the last 20 years or so, there has been a huge wave of interest and activity around what is often referred to as the “science of learning”. People’s understanding of this term varies widely - in a recent review of 50 papers on the science of learning, they found 43 unique definitions!

But mostly, it’s fair to say that when people talk about the science of learning, they’re talking about “cognitive science”, or “cogsci”.

To give just one example, a recent report called The Science of Learning by Deans for Impact opened thusly:

“The purpose of The Science of Learning is to summarise the existing research from cognitive science related to how students learn, and connect this research to its practical implications” (emphasis added).

Typically, people who write and think about the “science of learning” focus on various aspects of cognition - things like attention, cognitive load, deliberate practice, domain knowledge, forgetting, long-term memory, retrieval practice, schema, working memory - to name just a few.

We can also see a strong emphasis on cognition in the three definitions of learning above.

What’s the problem?

Broadly speaking, I think the cognitive turn has been a really positive, long-overdue thing which reflects a much more confident, sure-footed, research-informed teaching profession.

However, I’m concerned all this focus on cognition and memory overlooks something incredibly important about human development.

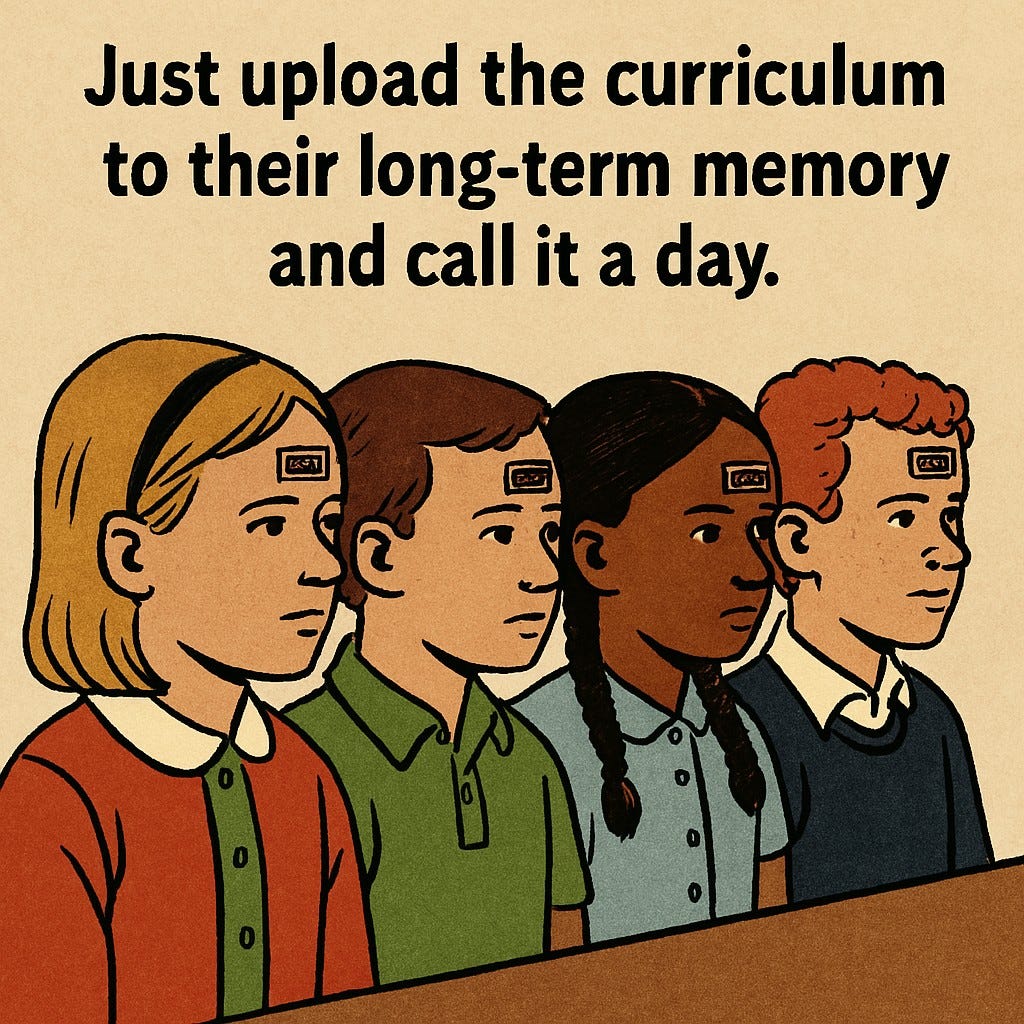

As I read and/or listen to the endless blogs, books, newsletters, podcasts and conference talks about the science of learning, it sometimes feels as though the entire process of education - this glorious project of human development - has been reduced to a question of information transfer.

There is information in the curriculum, and the teacher’s role is to effectively and efficiently transfer that information into the long-term memories of their pupils.

I’m not talking down cog sci or the teaching of subject knowledge. Of course it’s important to acquire knowledge and to build up a detailed understanding of the world. Knowledge is the stuff we think with: it’s the raw material that makes creativity and critical thinking possible. And of course subject disciplines are a really useful way to break up the world into more easily digestible units.

But - and this is such an important point that I’m going to crack out some weird formatting and a provocative meme:

There

is

more

to

human

development

than

the

learning

of

subject

knowledge

The science of learning… what exactly?

The aims of the “science of learning” appear to be twofold: learning to know (knowledge of subjects) and learning to do (associated skills). For some hardliners, even this second category is dubious, with skills being rebranded as ‘procedural knowledge’.

But there is a third kind of learning which does not get nearly enough air-time in my view, and which I think is arguably the most important of the three: learning to be.

Since alighting on this phrase “learning to be” a week or so ago, I've been compiling a list. Here are some examples:

Personal qualities and character

Learning to be a confident speaker

Learning to be consistent

Learning to be courageous

Learning to be disciplined

Learning to be healthy

Learning to be honest with yourself

Learning to be intellectually humble

Learning to be patient

Learning to be responsible

Learning to be self-directed

Learning to be someone who changes their mind when new evidence comes to light

Learning to be trustworthy

Interpersonal and relational

Learning to be compassionate

Learning to be empathetic

Learning to be ethical

Learning to be funny

Learning to be generous with what you have

Learning to be a good friend

Learning to be helpful

Learning to be kind

Learning to be persuasive

Learning to be playful

Learning to be polite

Learning to be useful

Learning to be vulnerable

Emotional and mental wellbeing

Learning to be at peace with yourself

Learning to be balanced

Learning to be comfortable with discomfort

Learning to be connected to nature

Learning to be grateful

Learning to be mindful

Learning to be present

Learning to be reflective

Learning to be still

Thinking and learning

Learning to be an effective learner

Learning to be a critical thinker

Learning to be curious

Learning to be eloquent

Learning to be expressive

Learning to be imaginative

Learning to be observant

Learning to be open-minded

Learning to be sceptical

To delve a little deeper, let’s briefly alight on three of the items above:

1. Learning to be someone who reads every day’.

Schools take the teaching of reading very seriously, and in recent years, we’ve seen an improvement in reading outcomes among young people. However:

40% of adults haven’t read a single book in the last 12 months (YouGov)

Only 43.4% of kids aged 8 to 18 enjoy reading in their free time, the lowest level since 2005 (National Literacy Trust)

In general, we do a pretty good job of teaching people how to read in schools. But to what extent are we succeeding and teaching people how to be readers?

2. Learning to be sceptical

How to put this delicately… In recent years, we have seen increasing evidence that people are somewhat susceptible to information of dubious origins and intents that they encounter in their social media feeds. I’m sure I don’t need to litigate this with examples.

In general, schools are pretty good at teaching subject knowledge. But to what extent are we succeeding at teaching people how to be more sceptical, discerning consumers of knowledge?

3. Learning to be kind to yourself

We don’t need to rehearse the fact that we have a severe and ever-escalating mental health crisis among children, young people and adults. Mental health is complex and multifactorial, but one significant factor is that many people treat themselves quite harshly. Many people have a critical, berating inner voice that frequently tells them ‘You’re stupid / ugly / everyone hates you’ and so on.

In general, schools are staffed by people who are loving and caring. But to what extent are we succeeding at teaching children and young people how to cultivate compassionate curiosity? To what extent are we good at being kind and less judgmental to ourselves?

Some counter-arguments (and counter-counter arguments)

I suspect that this post may elicit a strong response from some quarters, and so in closing I’ll see if I can anticipate any objections to this ‘learning to be’ agenda and nip them in the bud. I’ll also share a concrete example of what I’m talking about.

1. ‘How do you teach this stuff?’ This all sounds lovely, but the things in your list are too vague or abstract to teach. Schools are under pressure to deliver measurable outcomes. Isn’t this a distraction from the ‘real’ curriculum?

We teach these things all the time – just not always explicitly. Children learn what it means to be kind, patient, reflective, or curious through relationships, routines, stories, role models, and the culture of the classroom. Making it more explicit will help us to do it better – and more equitably.

2. How do you assess it? ‘Learning to be still’ sounds rather very woolly and difficult to measure. If we can’t measure it, how do we know it’s working?

What matters most isn’t always easy to measure. We can still gather rich evidence through observation, portfolios, self- and peer-assessment, reflective writing, or structured conversations. And besides – some of these qualities are worth pursuing whether or not they’re measurable. After all, we don't assess love or wisdom with a rubric.

3. Haven’t we heard all this before under other names – ‘grit’, ‘resilience’, ‘personal development’? Isn’t this just character education with a new label? Why do we need another framework?

This isn't a framework – it's a reorientation. 'Learning to be' invites us to treat personal development as a central goal of education, not a bolt-on. It asks not just what children know or can do, but who they are becoming. That shift in emphasis has important consequences for the kind of people - and the kind of world - we want to create.

4. There’s no time – we have a packed curriculum already. Teachers are overwhelmed. Isn’t this yet another thing to add to the pile?

Learning to be doesn’t require a new subject or a new initiative. It’s about bringing intentionality to what’s already happening. Every interaction, every feedback conversation, every choice about what to prioritise sends a message about who and what we value.

5. This all sounds a bit hand-wavy. Isn’t this just vague, feel-good fluff? Where’s the evidence?

There’s a growing body of research linking qualities like curiosity, self-regulation, purpose, mindfulness, and emotional literacy with long-term wellbeing, academic success, and social outcomes. These things matter – not just morally, but practically. This stuff takes place squarely within the ‘science of learning’ - provided we expand the definition to include non-cognitive aspects of human development such as physical wellbeing, habit formation, and relational learning.

What does ‘learning to be’ look like in practice?

To reinforce this final point, in closing I’d like to share one small piece of evidence that came to light this week.

Over the last couple of years I’ve been working with Welsh government on a project to promote learner effectiveness in secondary schools. Working with a steering group of 17 system leaders from a range of settings, we’ve created two sets of complementary resources - a professional learning programme for teachers, leaders and support staff, and some learner-facing resources. On Monday I’m presenting at the last in a series of 12 leadership events, where I’ve been sharing these resources with school leaders from across the sector.

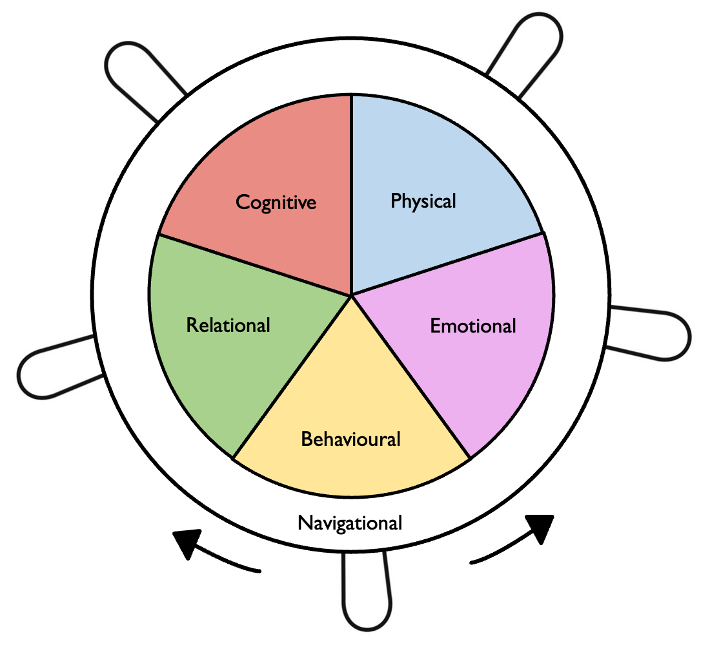

The whole thing revolves around a multidimensional ‘Ship’s Wheel’ model of learner effectiveness, which comprises six domains: physical, emotional, behavioural, relational, cognitive, and navigational. I wrote about this model recently here and here.

I was honestly expecting to meet a bit of resistance at these leadership events, but these resources - and the Ship’s Wheel model - have been incredibly well-received.

Some of the steering group schools have been trialling these resources already, and this week I received some feedback from a school leader who has been using them in her school. Here’s what she had to say:

“Quite a few teachers have chosen to use the breathwork and the breathing exercises. And they’ve actually tracked the impact on pupil behaviour in ClassCharts. There are three particular difficult year 10 students who have had a lot of issues in the last couple of months. And since they have been using these breathing exercises, their behaviour points have more than halved in their lessons. And I’ve spoken to them about it, and one of them told me how they use it in their rugby games. If they think they’re going to be in trouble and they think they’re going to act out, they use these breathing exercises. I actually observed a lesson on Monday and I witnessed one of those students telling someone else in the class to breathe in for 8, hold for 8 and breathe out for 4 seconds! So I think for me, the breathing exercises are something that we’re definitely going to incorporate in form time in the mornings. Now that teachers can see the impact that it’s having and how it’s improving behaviour…”

I suppose you could describe breathwork as a skill - ‘learning to do’ the 8-8-4 technique. But this is really a ‘learning to be’ thing - learning to be more mindful, more in control, less impulsive.

This might sound like a small example. But if three pupils are regularly disrupting lessons, that affects the learning of many other pupils. And so the effect of reducing the behaviour points of these three students by more than half could potentially have a huge impact on learning outcomes - not just for them, but also for their peers.

This is just one example of a ‘learning to be’ strategy we’ve been trialling in schools through this project. So far, we’ve developed 72 strategies - 12 for each of the 6 categories of the ship’s wheel. It’s early days - but the green shoots are starting to sprout.

An invitation

What would it look like if every school treated learning to be as a core part of its purpose and practices?

What if every teacher asked not just What do I want my students to know and do?, but also Who are they becoming?

What if our curriculum helped young people become curious, connected, kind to themselves and others – not by chance, but by design?

I’d really like for this to become the next frontier in the science of learning. I’d love for all my brilliant colleagues who write so well about memory and retrieval and so on to turn their attention to non-cognitive stuff for the next few years.

I think if we do this, we’ll truly be giving current and future generations the best possible preparation for navigating this wacky old world of ours.

Thanks for another provocation. I think your suggestion regarding cognitive science is spot on. Being is so important. Learning to care, be curious, courageous etc do require time. Whilst your suggestion that this is not another subject it does suggest to me that if there is too much content to ‘deliver’ there is unlikely to be time for young people to exercise their own curiosity or work out what they care about and why.

I recently observed some lessons in a different school, something didn't quite feel right in the room; what was missing was a sense of a class of leaners who had a sense of togetherness, where they were encouraged in oracy ; instead there was a procedural "well laid out" learning. Some vitals dimensions of learning to be were absent....I found myself getting impatient and bored..I wondered how the young students would describe thier class. Where was the fun, the mutual recognition, the excitement?