There is more to human development than learning about subjects

This feels like a strange thing to have to point out, but we are where we are...

That there is more to human development than learning about subjects featured centrally in my last post, but having reflected on it over the last couple of weeks, I feel this idea deserves a little more space to breathe - partly because it's such an important, true, and strangely overlooked idea, and partly to explore the implications of what this means for schools. (By the way, this post applies mainly to secondary schools, although the essential idea is applicable to primaries also).

School timetables are divided into subjects.

This is a strange sentence to write. It seems unnecessary to mention it because it's so widely understood and accepted. Disciplinary learning is just what schools do, almost all of the time. It’s the water we swim in.

In secondary schools, the notion of subject learning runs to the very heart of a teacher's identity. You aren't a teacher - you’re a teacher of science, or history, or drama or whatever. There are - for now, at least - no non-disciplinary routes into secondary teaching. You pick a lane, and then, mostly, you stay in it.

It is, of course, perfectly sensible that an education system should divide the world into subjects. You can't study everything all at once, can you? Dividing the world into subjects makes the task of learning about it so much more manageable. Within subjects, there are of course many further sub-divisions. In science, for instance, beyond the broad disciplines of biology, chemistry and physics, we find topics such as cells, solubility and space.

Because this practice of conceptualising education as a set of subjects and sub-topics to learn about is so widespread - and because so few schools deviate from a curriculum based exclusively around disciplinary learning - to point out that ‘there is more to human development than learning about subjects’ seems somehow subversive. But it really shouldn't be controversial to say this. It is simply a fundamental fact that is all-too-often overlooked.

In the remainder of this post, I’ll explore three related ideas:

There is more to human development than learning about subjects.

There are many incredibly valuable educational activities that don't fit neatly into subject-shaped boxes.

All schools should set aside time for non-disciplinary and interdisciplinary learning, alongside traditional subject blocks.

Let's dive in!

1. There is more to human development than learning about subjects.

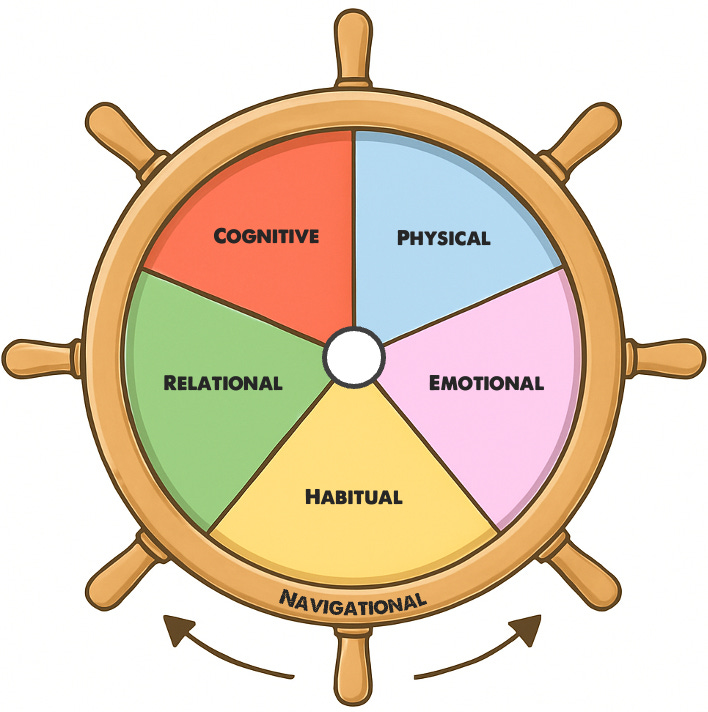

One way to illustrate some examples of non-cognitive learning is to consider the ‘life wheel’ model of learner effectiveness that I’ve been working on recently as part of a national initiative with the Welsh government.

Figure 1. The ‘life wheel’ model of learner effectiveness

As you can see, this model has six domains. I explored this in detail in a January post – click the link above for the full-fat version. Briefly, the idea is that in order to be effective learners and happy, well-rounded human beings, children and young people need to grow and develop in the following six domains:

Physical – to be effective human beings, students need healthy routines around sleep, nutrition, exercise, and daily practices like sport or stretching. It’s also important to pay attention to the physical environment: students need somewhere to study that’s quiet, comfortable, well-lit, organised, and free from distractions.

Emotional – first, emotional literacy: knowing and naming how they feel about themselves, school, and life, and recognising the emotions of others. Then, self-regulation: checking in, choosing strategies, and building routines that help them manage and process their feelings.

Habitual – acquiring the habits of effective learners such as time blocking, task management, and useful systems and routines, while tackling obstacles like procrastination, distraction, and addiction to technology.

Relational – relating to self (self-talk and self-belief), to others (communication, listening, teamwork), and to the wider world (awareness of current affairs, linking school to future life, understanding how we influence the world and how the world influences us).

Cognitive – learning about the world, understanding how the brain learns and how memory works, and developing strategies for the effective study, reinforcement, recall and transfer of knowledge and skills.

Navigational – setting goals, clarifying where you are now and where you want to be, and planning how to get there. All six domains - and especially this one - require a degree of learner agency, allowing each student to try a range of tools and strategies, to find out what works for them in order to become a more confident, proactive, self-regulated human being.

(By the way, the life wheel is not presented as a comprehensive system for human flourishing. For example, you could argue that there should be a moral/ethical wedge, or spiritual, or financial or whatever. But we can park this question for now. The aim here is simply to establish that there are multiple non-cognitive domains - i.e., domains which lie beyond the remit of subject learning - which are essential to healthy human development).

If the life wheel were a roulette wheel, it would be fair to say that schools have pretty well gone ‘all in’ on the cognitive wedge. Think of the ideas and the language that have dominated the education debate over the last 15 years or so:

Assessment for learning

Cognitive science

Curriculum mapping

Deliberate practice

Desirable difficulties

Dual coding

The Ebacc

Explicit instruction

Feedback

Flash cards

Interleaving

Knowledge-rich curriculum

Mastery learning

Mind maps

Non-examples

Progress 8

Retrieval practice

Rosenshine’s principles of instruction

Spaced practice

Worked examples

Working memory

All of these ideas are situated firmly within the cognitive wedge. As is the lexicon that defines a teacher’s life:

Curriculum maps

Data drops

Differentiation

Exam specifications

Grade boundaries

Learning objectives / outcomes

Marking policies

Mock exams

Past papers

Progress checks

Standardised tests

Success criteria

Target grades

Tracking spreadsheets

With the exception of tutor time and assemblies, the stuff of schools is pretty much cognitive, all the way down.

To be clear, this is in no way surprising. Schools are judged according to exam results - and they too reside in the cognitive domain. And of course we want all young people to function effectively in the cognitive domain - to understand the world around them, and to gain qualifications.

However, if a student’s barriers to learning are located elsewhere – if they aren’t getting enough sleep… if they’re making up for that fact by chugging a 500ml can of Monster for breakfast… if they’re hopelessly addicted to social media, or to gaming… if they have a chaotic social life, characterised by constant drama and falling out with their friends… if they experience lots of negative self-talk, or carry around limiting self-beliefs… or if they have (as many do) some combination of issues such as these – then focusing almost exclusively on cognitive factors such as subject learning, retrieval practice and exam technique is going to be of limited use.

In my work, I see this pattern playing out in schools all the time. Teachers plan amazing lessons and teach as well as they can, but often it doesn't ‘go in’ - not because of a cognitive deficit, but because students are not functioning effectively in the other domains.

I could go on about this all day, but hopefully by now I’ve made the point that there is more to human development than learning about subjects. Much more. Let's now look at some tried-and-tested examples of what non-disciplinary and interdisciplinary learning look like in the context of mainstream secondary schools.

2. There are many incredibly valuable educational activities that don't fit neatly into subject-shaped boxes.

Fifteen years ago, in the heady days of summer 2010, I was appointed to join a team of five teachers tasked with designing and teaching a taught Learning Skills Curriculum (LSC) at Sea View, a state secondary school in the south of England. We were given 5 lessons a week with the whole of Year 7, and we could do with this time whatever we wanted - whatever we thought the students needed to get better at this whole learning malarkey.

Later, these timetabled lessons expanded into Year 8 and then again into Year 9: over a 3-year period, those young people took part in over 400 lessons of non-disciplinary and interdisciplinary learning.

What did we do with all this time? Well, as you might imagine, we did loads of things - some that worked really well, others less so, as you might imagine. Here are a few examples that did work well:

The “Who am I?” project

In the first half-term of Year 7, we gave students 6 weeks (using 3 of the 5 lessons a week, plus homework) to answer this question in as many ways as they could muster. We gave them very little guidance, beyond a one-page project brief and the occasional coaching conversation if they got stuck or wanted some feedback. Some created a booklet with various sections - a family tree, an interview with a family member, a letter to their future self - that sort of thing. Some created a slide deck with a timeline of their childhood, photos of their friends and places they'd been, favourite books and films and so on. One girl created a 3-D model of her house, which contained lots of tiny figurines of family members, pets and so on, and she made little cards with information about various items in the house that said something about her life. It was really quite something. At the end of the half-term, each student presented their project to the class.

This is a wonderful thing to do as a transition project, either at the end of Year 6 or the start of Year 7 - or both, if you can coordinate your efforts across primary and secondary schools. It allows teachers to get to know their students - and students to get to know one another - on a whole other level. And students develop independent learning skills, and gain confidence through public speaking, in a way that feels achievable and safe because the subject matter is something they’re already the world-leading expert in - their own lives.

You can do this within English lessons - I’ve worked with schools that have done this - but it also works really well as a standalone project within a broader curriculum framework such as the LSC.

Building and growing an allotment

In Year 8, we gave each group the task of building and growing an allotment bed. This required digging up an unused area of grass and building allotment beds using old scaffolding planks. We gave each group a small budget and took them to B&Q to buy seeds and bulbs and soil. We even built a greenhouse out of recycled plastic bottles.

I strongly believe that eating food you’ve grown yourself should be a regular feature of every young person’s life. It’s an incredibly life-affirming, grounding thing to do, and it’s not something that’s easy to achieve at scale in the context of science lessons, say. It really needs time to take root, so to speak.

The £2 challenge

For this enterprise project, we gave each student £2, told them the Bible story of the Parable of the Talents (it wasn’t a faith school but it seemed appropriate), and challenged them to grow their money in order to fund a school trip to a destination of their choosing. Again, we provided them with little guidance beyond some basic ground rules (they weren't allowed to buy and sell sweets as this wasn't in keeping with our status as a ‘Healthy School', and they had to keep receipts and track how their money grew across the 6-week period).

Some students bought a bucket and sponge with their £2 and washed their family’s and neighbours’ cars. Others bought and sold bottles of water and gradually made more profit as they reinvested their earnings. One girl bought some jewellery blanks and glue, and asked people to donate unused Lego and Scrabble pieces. Then she made an industrial amount of rings, brooches and earrings that she sold for eye-watering profit. (She kept this little side-hustle going for years, and would rake it in whenever there was an open evening or coffee morning.)

Initially, the students wanted to go to Paris, but when they worked out how much it would cost, the destination was revised to a local theme park. They shopped around for the cheapest coach deal… they wrote and distributed letters to parents and carers and collected in the consent slips… they even wrote the risk assessments. This project led me to seriously shift my expectations about what young people are capable of when you give them the opportunity and the responsibility to make things happen.

Interdisciplinary research projects

We did a few library-based research projects, and found that it generally worked better in groups than with individuals. It’s easier to keep the momentum going when there’s ongoing dialogue, I guess.

In one 6-week project in Year 7, students worked in groups of three and chose topics from a curated selection of library books on topics such as politics, culture, and global history. They could either choose one topic, or they could combine a few topics together if they wished.

In one group, each student quickly formed a strong attachment to three very different areas of interest: feminism, South America, and China. After some discussion, they realised they could combine their interests into a project titled ‘A comparative study of the history of feminism in South America and China’ (!) Over the next few weeks, they explored complex themes such as communism, equality and revolution, issues such as foot binding and the one-child policy, and key historical figures like Eva Perón and Frida Kahlo. This project really made me realise how, once children can read independently, open-ended interdisciplinary inquiry can lead to the acquisition of powerful knowledge and understanding that is not cultivated through a traditional subject-based curriculum.

Philosophical inquiry

Philosophical inquiry, often referred to as Philosophy for Children (P4C), is a structured approach to developing students’ thinking, reasoning, and dialogue skills through extended philosophical discussion. Sessions often begin with a stimulus, such as a short story, and image, or a piece of music, which is used to spark reflection and generate questions.

Personally, I find it’s just as effective to ask students to share the big questions they often carry around in their minds, or which quickly surface if you give them a little time and space. Either way, you come up with a list of questions, and students then vote on one question to explore in depth - ideally one that opens up space for extended discussion about big ideas like fairness, identity, human nature, or the nature of reality.

The class sits in a circle to form a ‘community of enquiry’, and students take turns to share, build on, and challenge one another’s ideas. The teacher acts as a facilitator, guiding the discussion through gentle questioning to encourage deeper thinking, and managing the group dynamic without dominating the conversation. Dialogue is co-constructed and consensual, with an emphasis on reasoning, respectful listening, and building on the ideas of others.

Once students have developed the habit of using a hand signal if they want to speak, and choosing the next person once they have finished, these sessions can really start to flow and you can enter an extended period of extended discussion with little or no need for input from the teacher. It also helps if pupils are firstly taught basic critical thinking skills, such as how to build arguments, identify faulty assumptions and logical fallacies, and ask good questions.

People often talk about how P4C can be incorporated into subject learning - when discussing some deeper elements of English, Science, geography, history, art, RE, music and so on. This is true, and I heartily encourage it. But it shouldn’t need to be shoe-horned in to an exclusively subject-based curriculum. Engaging in extended philosophical dialogue is an incredibly valuable and important educational activity in its own right, and I really think it deserves a weekly slot in the timetable all of its own. it’s a great way to end the week - as with the related idea of Making Sense lessons, which I wrote about recently.

Debating

It takes a long time to organise a single debate, if you do it properly. At Sea View, we would spend five full lessons preparing for and running just one debate involving five speaking roles: one chair, two arguing for the motion, and two against. To allow each student in a class of 30 to experience having a speaking role, we ran this cycle six times over a 6-week period. It would be possible to streamline this process a little, but even so, this would not be realistic within the time constraints of subject learning.

If we want all students to become experienced and skilled in a range of debating formats – as is common in the elite independent schools that educate so many of our political leaders – we need to set aside curriculum time for this important work to take place. Elite independent schools have produced dozens of prime ministers and countless other influential figures – not only because they are rich and well-connected, but because of the quality and quantity of debate training they receive, which is essentially training for when they get to run the country. If we want a political class that draws on the full talent pool of the human population - and a cursory survey of the people who have dominated public life in recent years suggests that this might not be a terrible idea - we need to ensure that regular, structured debating is available to all – not just those with parents who can afford to pay for it.

Public speaking

Related to the above, fear of public speaking is widespread – for many, it ranks even higher than the fear of death(!) While extreme cases of glossophobia are rare, most people experience some anxiety when speaking in front of others, especially in high-stakes situations. This fear is understandable and often driven by inexperience. The most effective way to overcome it is therefore through gradual exposure.

At Sea View, we supported students to build confidence by allowing them to start small – presenting to just a few peers or a teacher – and slowly increasing the level of challenge. Presentations were a regular, expected part of project work - every half-term ended in a ‘teachable moment’, followed by constructive peer feedback to help the students develop their rhetorical prowess.

Over time, even the most nervous students rose to the challenge, buoyed by a sense of achievement and the visible confidence boost it brought. The key is not to force public speaking on students, but to encourage and support them patiently and persistently so they can succeed. It’s fine to go through life choosing not to speak publicly – but that choice should not be driven by fear or lack of opportunity. With the right support and training, the vast majority of students can learn to become confident public speakers – a skill that can transform their sense of who they are and what they might go on to achieve in the future. Again, this takes time and it’s not easy to see how this can be achieved in the context of subject learning - partly because of time constraints, and partly because not all teachers are experienced in public speaking themselves, let alone teach it to others. It’s far more efficient and effective to outsource this to a non-disciplinary department dedicated to such things.

The list goes on

The LSC included things like meditation, exploratory group talk, writing in learning journals, and a wonderful (and now sadly discontinued) level 2 qualification called Thinking and Reasoning Skills. And beyond the LSC, there are many examples of non-disciplinary and interdisciplinary learning that take place in schools around the world, albeit a tiny minority. Perhaps I’ll do a round-up of these in a future post.

For now, I hope the point has been made - there are many incredibly valuable educational activities that don't fit neatly into subject-shaped boxes. Before we move on to the practical implications for schools, let’s briefly address a question that I suspect may have arisen in at least some readers’ minds:

What was the outcome of all this non-disciplinary and interdisciplinary learning?

In my head, there is a tiny trad who lives rent-free, asking annoying questions. Things like:

This all sounds well and good, but what about their grades?

And:

Aren't you sacrificing their futures on the altar of an outdated and discredited progressive ideology?

Well, mini-trad, you may (you definitely won't, you incurious little monster) be interested to learn that those students who took part in the LSC went on to achieve the best GCSE results that school had ever achieved, by some margin. Furthermore, those gains were most pronounced among children from under-resourced backgrounds. In the control group (the previous year group at the same school, who had very similar data at entry to the school, so it made for a nice fair comparison) the disadvantage gap at the end of Year 9, across all subjects combined, was 25%. In the first LSC cohort, following more than 400 lessons such as those outlined above, the gap was just 2%. And we saw a very similar pattern of results 2 years later, when they sat their GCSEs. Best results ever, and a huge closing of the disadvantage gap from the bottom up.

If you want to know more about the LSC at Sea View, I wrote a book about it a few years ago with Kate McAllister, called Fear is the Mind Killer (2020).

Since then, we’ve helped schools implement the LSC in various countries around the world (not so much in England… yet!), with a similarly positive impact on learning outcomes. For example, check out these two short videos outlining the impact of the LSC at Knysna High School in South Africa - an initiative that followed the 5 lessons a week model:

I’ll draw this post to a close with the third point, about what all of this means for schools in practice.

3. All schools should set aside time for non-disciplinary and interdisciplinary learning, to take place alongside traditional subject learning.

Subject-based learning is great. Really. I love it to bits. But it’s not the only game in town – or at least, it shouldn’t be.

In recent years, much has been written about the importance of a knowledge-rich curriculum. Within the context of subject learning, this makes sense. But as with food, a diet of learning can be a little too rich in some elements, and lacking in others.

That’s why I’ve argued for thinking about curriculum in three ways: learning to know, learning to do, and learning to be (sometimes called education of the head, hand, and heart). However you prefer to name it, schools need space for non-disciplinary and interdisciplinary forms of learning to sit alongside the traditional, subject-based curriculum.

Whenever I’ve suggested this in the past, people often respond: “OK – but what would you get rid of? Which subjects or topics are unnecessary?” But in the LSC, we didn’t remove any subjects or topics. Because the students had become more effective learners, they were able to learn the same material - actually, more of it - in fewer lessons.

The journey to a more well-rounded, truly broad and balanced curriculum begins when a leadership team takes the brave decision to allocate time on the timetable to non-disciplinary and interdisciplinary learning. There is no one way to do this - but all schools can take steps in this direction. Kate and I don’t suggest that every school does what we did – if I had my time again, there are loads of things I’d do differently. But we are by now old hands at helping people find their own way.

If you’re a school leader and you’d like to explore the practicalities, feel free to drop me a line. And if you’re a parent or carer who’d like to see a broader curriculum offer for your child, perhaps you might forward this blog to your local headteacher or trust CEO. You never know, it might just catch on. I really hope it does.

What do you think? Do you agree that all schools should set aside time for non-disciplinary and interdisciplinary learning? If not, why not? I’d love to hear your thoughts!

I love my Saturday morning think. Thank you James. You may be right if you are only trying to integrate subjects with a focus on knowing then there can be time. But if you want students to have the experience to authentically do and learn how to be a scientist, designer, historian then this requires a shift of the qualification. Efficiency has some element as you suggest but effectiveness to wayfind and iterate means we can't do the same amount of subject content. The Crossfields Institute have a fabulous integrated extended diploma at Level 2 (GCSE) and 3 (A Level). I think this supports the piece about human development really elegantly.

This piece is a cracker, James and I loved the little twist in the tale at the end. I taught at a primary IB World School for two years and their approach of transdisciplinary inquiries could be amazing when done well. I think there is one wrinkle in what you write about open-ended interdisciplinary research projects - "once they can read independently" you rightly say.....and really being able to do that is something we need to prioritise to open up those opportunities.