From critique to action: Seven practical ideas to improve education

What would you add to this list? What would you change?

In this post I’d like to offer a quick round-up of my work over the last 12 months or so, which has really been marked by a shift from critique to action. The rationale for these reforms comes in two parts.

There is an educational polycrisis. Wherever you look - attendance, mental health and wellbeing, teacher recruitment and retention, misogyny and sexual abuse, racism, bullying, the disadvantage gap - the alarm bells are sounding loud and clear that despite its many virtues - and there are many - school-based education needs to change. Fast. Many people - children, young people and educators alike - are suffering because of the way in which the system is currently configured.

There are many things we can do that would massively alleviate the problems listed above. Here are seven practical ideas that I think would make everybody’s lives a whole lot better. In some cases, these ideas are already happening and evidence of impact is emerging - it’s more a question of scaling up. In no particular order:

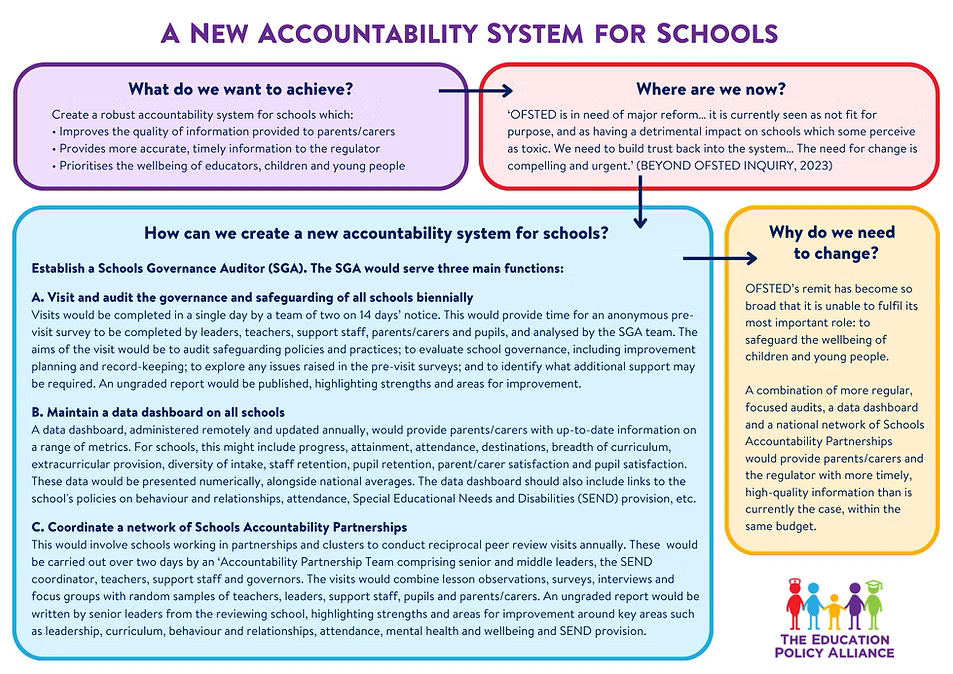

Create a new accountability system for schools. Ofsted has proven incapable of meaningful reform. After a somewhat hollow ‘listening exercise’, its new system for grading schools feels eerily and wearily familiar. We need to put this toxic, school-shaming machine out to pasture and replace it with something more collegiate and supportive. Many high-performing countries don’t have an Ofsted. We can live without it, if we replace it with something sensible.

Last year, the Education Policy Alliance (EPA), a grass-roots think tank of which I am a member, published a report outlining a vision for a new accountability system for schools. Here’s a one-page snapshot - you can read the full report here (scroll down to the Jan 2024 entry).How would this help? Replacing Ofsted with a peer-led accountability system would replace a culture of fear and compliance with one of trust, learning and support. By increasing the frequency of safeguarding audits to every other year - an idea that headteachers I have spoken with fully support - it would make children and young people safer. (Previously, many schools went more than 15 years without an inspection. Ofsted now aims to bring this down to 5 years. But a lot can go wrong in 5 years…) And by reducing the anxiety and workload associated with high-stakes inspections, it would improve staff wellbeing, reduce attrition, and allow schools to focus more on what really matters: helping every learner thrive. Which brings us neatly to…

Make wellbeing our north star. For years, almost all activity in schools has centred around the mission to optimise exam grades. Even the recent embrace of research and evidence-based practice, which has much to commend it, ultimately increases pressure on teachers and students to perform - to demonstrate that exam results are getting ever-better. All of this is done with the best of intentions - but the side-effects are impossible to ignore. To offer just one example: the proportion of English pupils saying they dislike school has doubled in the last 8 years.

The EPA recently wrote a report outlining our vision for how we can turn this around. It’s called Everybody Thriving: Creating a Culture of Wellbeing in Schools - see the one-pager below.This week, we received a written response from Stephen Morgan, the Early Years minister. The government does seem to recognise that wellbeing is a burning issue and that to remedy this, “all pupils need to feel included, heard and valued”. But this is easier said than done - meaningful pupil voice, such as the astonishing clip I published last week about a Year 3 pupil shaping school policy, is the exception rather than the rule.

To be clear, prioritising wellbeing is not about lowering expectations or protecting pupils from ever experiencing discomfort, as some people seem to think - quite the opposite. It’s really about taking pupil voice seriously, and finding ways for students to be more agentic and to shape their own educational journey. More on this below.

How would this help? By placing wellbeing at the heart of school life, we would tackle the root causes of poor attendance, burnout and disaffection.

If you’re able, come to our low-cost Manchester ‘unconference’ on Saturday October 11th. It’s also now possible to access the conference remotely for those of you farther afield - sign up and see more details here!

Make oracy ordinary. Recently, the Oracy Education Commission published an excellent report outlining why oracy should be considered the fourth ‘r’ (alongside reading, writing and arithmetic). The arguments in favour of giving spoken language equal weight to written literacy and numeracy are legion. Some traditionalists argue that spoken language is “biologically primary”, with the implication that it therefore doesn’t require teaching. This claim is difficult to take seriously given the clear evidence that oracy skills can be taught – and taught well – with wide-ranging benefits for learners, not least the life-changing sense of confidence and self-belief that comes with increasing your mastery of spoken language.

Yesterday I went to the annual Oracy Cambridge / Voice 21 conference on ‘Exploring excellence in oracy education’. It was an amazing day. In her keynote, Alison Peacock said (I paraphrase): “In recent years there has been lots of emphasis placed on cognitive science. But oracy is fundamental to the development of cognition. This is not a side issue.” Good point, well made.The case for making oracy ordinary is building - we’ve never been in a stronger position to make the development of spoken language a feature of ‘the way we do things around here’. But there are many ways in which this moment could slip through our fingers. The absence of oracy from the Curriculum and Assessment Review’s interim report was puzzling and deeply concerning. Behind the scenes, people ‘in the loop’ are saying there’s nothing to worry about. But I do worry. Let’s keep up the pressure, and keep banging the drum for this shift to take place - we’re almost there!

How would this help? When all children and young people are supported to find their voice - literally and metaphorically - marginalised groups are more likely to feel seen, heard and valued. This would help reduce racism, misogyny, and bullying, all of which thrive in silence and isolation. I once undertook an 8-year study of an oracy-based learning skills curriculum, which significantly improved subject learning across the curriculum - especially for disadvantaged students. Making oracy ordinary would help close the disadvantage gap without narrowing the curriculum or piling on pressure to perform.Implement a weekly Making Sense lesson. I wrote a blog last month (An easy win that would immediately make school more enjoyable and meaningful) suggesting this should be happening in every school. It would be cost-free, easy to implement, and act as a release valve for the pressure to perform that weighs so heavily on children and young people. Following this blog, many people got in touch to say they’d like to explore this idea further - and one school has already implemented weekly Making Sense lessons in Years 8 and 9! I’m going to visit in a couple of weeks, to hopefully film part of a lesson and to interview some of the learners and teachers. Watch this space!

How would this help? A regular space for reflection and shared meaning-making would help learners process their experiences and understand themselves, others and the world in which we coexist. In a time of fragmentation and polarisation, this simple change would restore a sense of coherence, belonging and connection.Implement a Weekly Review lesson. I wrote about this in my last post (The Weekly Review: Every school should be doing this), and shared some emerging evidence of impact. Over the last 2 years, I’ve worked with a group of 17 school leaders from a range of provisions throughout Wales to create a set of resources - the Learner Effectiveness Programme - which lend themselves nicely to a weekly review lesson (although they can be used in a range of other contexts also - tutor time, health & wellbeing lessons, small-group interventions and so on). These resources are being rolled out in schools across Wales from September, and I’m currently working with an international steering group - alongside my Rethinking Ed copilot Kate McAllister * - on adapting them for a range of contexts. Watch this space also!

How would this help? Weekly reviews help learners become more effective at learning by embedding metacognition and self-regulation – two of the most powerful levers for academic success. When students become more effective learners, everything improves – motivation, behaviour, attendance, achievement. Improving learner effectiveness also lightens the load on teachers, reducing the need for constant intervention, behaviour management and micromanagement. In turn, this would support teacher wellbeing and improve retention.Dedicate 20% of curriculum time to self-directed learning. The legendary Derry Hannam wrote a guest post on thse pages earlier this year (Should schools dedicate 20% of curriculum time to self-directed learning?) outlining how and why this should happen - and where it’s already happening around the world. As noted above, I myself was once involved in a 20% SDL initiative which significantly improved subject learning across the curriculum, and massively reduced the disadvantage gap. It didn’t cost anything and we have since replicated the findings elsewhere. Subject-based learning remains important and necessary - but it should not be the only game in town. Learning to know - sure. Learning to do - absolutely. But let’s not forget the importance of learning to be.

By the way, this 20% would include the ‘Making Sense’ and ‘Weekly Review’ lessons outlined above. The additional 3 lessons should be dedicated to self-directed learning. In my next post I’ll outline what these lessons might look like.

How would this help ? Self-directed learning allows children and young people to follow their curiosity, developing confidence and independent learning habits – qualities and attributes we all need to navigate an uncertain world. Giving students greater autonomy can also increase motivation, reduce behaviour issues and help close the disadvantage gap.Use the Making Change Stick framework to implement change. Currently, most schools use the EEF implementation guidance to implement change initiatives. Also: currently, most school improvement initiatives don’t actually, well, improve anything. Most of the ‘high potential’ projects the EEF have evaluated in recent years either had no impact on pupil outcomes, or made things worse. Clearly we need to change the way we change.

I recently wrote a book called Making Change Stick: A Practical Guide to Implementing School Improvement - the culmination of 10 years’ R&D. The word is starting to spread and requests are coming in thick and fast for support in implementing these ideas all over the world. I recently discussed with Ollie Lovell on the ERRR podcast how I’ve become increasingly radicalised in recent months. If you’re a school leader and you’re currently leading a change initiative, or thinking of doing so: DON’T! Just stop what you’re doing. The chances are that you’re going to use up a lot of valuable time and resource and that your initiative will either have no impact, or make things worse. I don’t think you should never try to improve anything ever again. I just think you should read my book before you do. Check out the free taster course here 🙂

How would this help? Systemic improvement isn’t just about what we change, but how we change. By adopting a more effective, evidence-informed approach to change, we would increase the chances of making meaningful improvements stick – reducing waste, frustration and initiative-itis.

Well, here endeth my round-up of suggestions for how we can improve the education system. Is there anything here you disagree with? What would you add to this list, and why? I’d love to hear your thoughts!

* Kate got so good at self-regulation, she now lives in the Caribbean. Be careful what you wish for…

Can’t disagree (nor would I want to) with anything you’ve written in this piece. Thank you for it and for sharing so many useful links. I’ll share it with PLACE network colleagues, supporting families on the ground experiencing issues around education (barriers) and poor mental health (often as a result of experience in the education system). Thanks for all you have done and continue to do for those still in the system and those still to come.

These seven reforms feel like a breath of fresh air—finally centering the human elements that make education meaningful. The shift from exam-grade optimization to wellbeing as a north star is especially powerful.

I’m particularly drawn to the emphasis on student voice and oracy. But it raises an important question: whose voices are we centering? When we make oracy “ordinary,” are we building on the rich communication traditions students bring from home—or asking them to perform a particular kind of speech to be heard?

The peer-led accountability system is also promising. But who gets to design it? Are we inviting the teachers most harmed by the current system, or mostly those who’ve succeeded within it?

And practically—while I love the idea of Making Sense lessons and Weekly Reviews—many teachers I know are already stretched thin. What do we remove or simplify to make room for these additions? How do we honor where educators are, not just where we hope they’ll be?

These ideas have real potential to humanize schooling. I’d love to see them developed with the communities they aim to serve—rooted in lived experience, not just designed around it.